When I originally came up with the idea of Political PT, I thought I needed to make it super objective and free from any trace of my personal political bias. I even went so far as to declare to myself that I was going to write in third person because somewhere in my cute little academically conditioned brain that’s what a good, noble writer would do. And of course I wanted this to be a good and noble space. I’m an eldest child. I have my doctorate degree. I’m an enneagram 1. Nothing I do can be any less than good and noble or else I’ll die and so will everyone I love. Obviously.

So, of course, every time I started writing, it sucked. The sentences were clunky and took forever to formulate because it felt so unnatural. Above all, they were boring as f*ck. So I let myself off the hook and started writing exactly what I wanted to say, how I wanted to say it. I figured that if my writing was going to turn out like sh*t I should at least try to have some fun with it. And you’ll never believe what happened next.

Not a single person died.

It also felt good in my bones. So I’m going to keep doing it. I’m going to keep letting myself off the hook when something is nagging at me to be written even though I have silently declared that the topic doesn’t match the ethos of my incredibly lofty, world renowned, award winning blog.

So this one’s going to be a think piece. If you’re strictly here for the explainers and don’t care to muse, then skip this one. I still love you for stopping by, and we can still be friends. And if we both die because I wrote about an anecdotal experience instead of how the federal government operates, I am deeply sorry.

This essay is about the political etiology of pain and how healthcare professionals have been taught to ignore it at the detriment of our patients.

I don’t know about you, but I’m seeing it. I see it mostly with middle to late aged women and full-time caretakers, two populations that frequently overlap and two populations that are frequently, how do I say this, treated like dogsh*t. Neglected by the system.

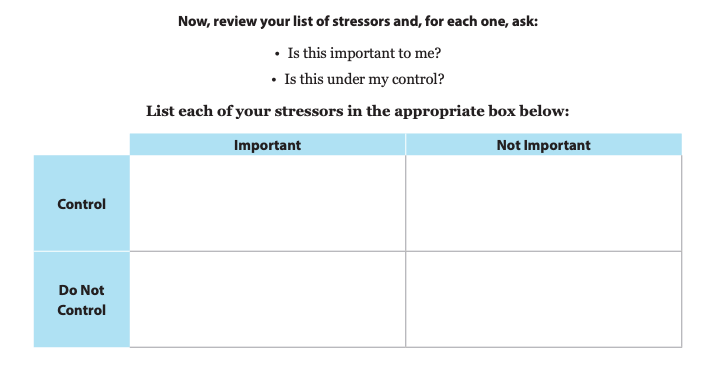

I have an awesome job that allows me the luxury of not only asking about patients’ stress levels, but also structuring a treatment plan that includes stress management. Lately, I have been using the VA stress management workbook (please share if you have any good recs that you use yourself). We start out by identifying stressors and categorizing them as “out of my control” or “within my control” using this handy little chart.

At the bottom of the page, the workbook gives tips on how to deal with the stressors based on where you place them in the chart.

“Let go of stressors that you identified as not important. They aren’t worth the stress they cause.”

“Take some time to address those stressors that you feel are important and that you do have at least some control over.”

I like those tips. They make sense. In my sessions, we do take time to address stressors that my patients have some control over. We make goals like spending 1 hour on organizing medical files that have built up on the dining room table or practicing grounding at least 3 times throughout the upcoming week when you notice yourself starting to get frustrated with your spouse. It’s productive and usually makes people feel empowered with a plan.

The problem I run into lies with the bottom left box. That motherf*cker always sends me into a spiral because it usually houses some hefty problems. Recently, it read “my husband won’t be able to get his meds if social security funding is cut.”

I stared at it. And then I stared at my patient. And then I stared at it. And then her. And the whole time I was scouring my brain for the appropriate response to that statement.

Surely with all the emphasis in grad school and the clinical field about the biopsychosocial model of care, someone would have told us it was okay to talk about these issues with our patients. But I couldn’t remember hearing any of that. I remember, “screen for it” and “refer out” and “don’t jeopardize the patient-provider relationship or, [God forbid], the business, by talking politics.” Ignore it. Deflect.

The only other option available to me at the time was to default to the tip for this box at the bottom of the page:

“Practice stress management techniques for the stressors that are important but that you do not control. You might also avoid these stressors or limit exposure to them.”

Sure. Let’s breathe 4 seconds in and 6 seconds out about how your husband might have his life threatened if the government stops subsidizing his meds.

Dismiss or downplay. Those were my two options.

No. F*ck right off with that. Quite honestly, I can’t imagine something more damaging the patient-provider relationship than having her write down something that vulnerable and then ignoring it or telling her to touch grass about it.

We have to do better. Maybe 20 years ago we could get away with ignoring political discourse in healthcare, but not anymore. There are scores of studies showing the relationship between the world in which someone lives and their health. Not to mention the direct relationship between stress and physical pain. We’re expected to educate people on pain neuroscience the context of the biopsychosocial model, but mentioning politics is still taboo?

Bullsh*it. In 2025, if I’m talking pain, I’m talking politics.

The next question is how? If you’re looking for the answer in the space of political commentary, you won’t find it. Trust me, I’ve looked. I’ve listened to the podcasts and read the articles. For the most part, it’s partisan cliques stuck in their respective political silos egging each other on. Every conversation is laced with the idea that their argument is more morally sound and the other side deserves to rot in hell. I won’t bore you with a paragraph about the same worn-out opinion that social media and the algorithms are pitting us against each other. We know they are.

The political atmosphere is hurting people. Like, causing them real, physical pain. At the same time, politics is synonymous with moral judgement. How do we unweave this emotionally charged knot so we can appropriately acknowledge and comfort each other? How do we shed the fear that’s been instilled in us by institutions that broaching the subject will impede, or even ruin, our careers? When did we decide that politics is a line we won’t cross in order to acknowledge the humanity in our patients? I don’t claim to have the answers to these questions yet, and I would love to hear your thoughts.

I do think that part of the solution starts with leveraging our own authority in patient-provider interactions. Not in an abusive or manipulative way, but in a way that clearly and firmly asserts that patients are safe to express their feelings around politics. This is especially important for those we treat whose opinions differ from our own. And I don’t know about you, but I am kind of exhausted with being personally offended by other people’s political opinions. It’s run its course. I’m ready to be productive instead of let my ability to empathize be slowly eroded by an emotional response that I’m not even sure is mine anymore.

When leadership at the highest level turns away from compassion and compromise, that sets the tone for how the entire country operates socially, whether you notice it our not. People are walking on eggshells, and sometimes I feel like the tension of the social environment causes more damage than the threat of policy change. Stress is a perception. People are not perceiving policy change every day. They are, however, perceiving the social environment.

We can’t necessarily change what’s happening in policy right now, but we sure as hell can influence the social context in which our patients perceive these events.

I’m not saying we should provide a rose-colored-glasses perspective, or even one that’s glass-half-full. In many cases that would be a lie. We could try to be the most diplomatic person in the room, but I think that approach is tone-deaf. It reinforces the narrative that it’s hard to find a healthcare worker who will actually listen to you.

I think that a healing environment is one that’s infused with humanity. What makes someone feel really safe is not just acknowledging their stress. It’s showing your hand. It’s being vulnerable in return and saying what you actually feel instead of hiding behind the professional status quo in the name of business. Because as much as the United States wants for it to be, healthcare at its core isn’t a transactional relationship. Healing depends much more on reciprocal relationships than our systems care to acknowledge.

If instead of deflecting we start taking up political conversations with compassion, respect, and curiosity, then I think we can slowly chip away at the immediate panic people feel when they merely hear the word “politics.”

Less of, “That sounds really hard. I’m sorry you’re experiencing that,” and more of, “I’m worried too. What about your life experience makes you believe that?”

Opening the door for compassion and curiosity sounds hard because it forces us to come face to face with rejection in the professional space. Will they cancel their follow-ups? Will they not like me after I say this? Could I be fired?

Maybe scariest of all: Could they change my mind?

I’m newer to the professional world. I’m also part of a generation that doesn’t really remember a time when people could talk about politics without condescension or moral shaming. Maybe more experienced clinicians have already adopted the mindset I described above. If this is you, please share some tangible tips. As you can see, I’m struggling so much I wrote a 1,600 word essay on it.

Any feedback can be left below. The aim of Political PT is to make political topics easier to understand and less scary to read about. I write about things through the perspective of a young woman in healthcare, but my articles are for anybody who wants to understand more about how things work in the U.S. government. I keep things light and witty, and I only send out articles every few weeks so you won’t ever be bombarded with click-baity headlines. Political engagement is a marathon, not a sprint, and political literacy is a huge piece of that. If this is something that interests you, subscribe to my newsletter. I can also be found on Instagram and Substack if that’s your jam.

Leave a comment